Cliff'd Out in Snowbird

May 4, 2011

May 4, 2011 This story, written by Marc T. is presented on AspenSpin un-edited....everyone survived, please don't call social services.

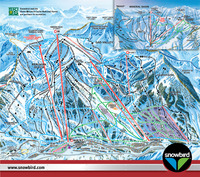

Snowbird. Click to enlarge.Peak Experience on Defiance Ledge

Snowbird. Click to enlarge.Peak Experience on Defiance Ledge

It was a bluebird day at The Bird, the last of four consecutive ski days with my son Jason. On top of a thirteen foot base, it had dumped a foot the previous day and there was not a single run closure. I had never seen Snowbird with such ideal spring conditions. For an eleven year old sea-level kid from San Diego, California, Jason is a very good skier while still lacking experience that can only be obtained from millions of turns in a variety of conditions. Displaying a fearless tenacity the previous three days on such legendary touchstones as Great Scott, High Baldy, Jaws and Mach Schnell, he had already conquered many runs that more experienced skiers view with trepidation.

Riding up Gadzoom we saw dozens of skiers in the high distance traversing along the Road To Provo toward the top of Gad 2 chair, which was closed for the season. We jumped on Little Cloud to the 11,000 foot Hidden Peak, banged a right, and 15 minutes later arrived at the top of Gad 2 chair amongst many other hounds in search of remaining powder. Our plan was to ski out the Red Lens Line (Knucklehead Traverse), heading west through the trees, and then down into glades with guaranteed powder into Thunder Bowl. I had been through this “in bounds terrain with an out-of-bounds vibe” many times and felt comfortable that it was within Jason’s ability. The ski patroller at the top of Gad 2 had recommended looking for a way down in the shade since it was pretty warm and the eastern facing slopes were set-up with avalanche potential. As we glided along the Knucklehead traverse, the path through the increasingly dense trees narrowed with a diminishing margin of error separating us from vertiginous drops on the right side, the type of situation where one little mistake carried scary consequences. I was starting to realize it had been a bad idea to bring Jason in there, especially after a skier in front of us yelled “don’t look down.” But it was way too late to turn back.

Father and son taming Ajax Mountain in Aspen.Other skiers started dropping off into sun-baked glades while we continued searching for a more northern-facing slope. At last we got to the western boundary rope, a spot I had never been to in all my years skiing Snowbird. There it was, the perfectly shaded untracked chute. I told Jason to go first knowing that if he fell, and especially if he lost a ski, it would be much easier if I didn’t have to hike up to bail him out. Sure enough, a few turns down he took a spill in some deep snow and was pretty dug in and twisted around. I released the binding of his stuck ski, packed down a semi-horizontal area on the steep slope and snapped his ski back on, concluding with a hopeful request to “please don’t fall again.”

I followed behind Jason for another several hundred vertical feet of fluff down Boundary Bowl when I noticed he had stopped a few turns below me on a 45 degree slope. And a few turns below the only traverse track. My heart skipped a few beats when I heard his little voice say “Dad, I think it’s a cliff” to which I instantly thought “oh shit” but instinctively replied “ok, you have to climb back up.” After trying a few times to take one small step uphill, only to slide further back down toward the cliff, I realized there was no way he would be able to hike up. Taking his skis off would be even more dangerous. Just as I was contemplating skiing down to him, he said “I might be able to get through but don’t come down here, there’s no way your (longer) skis will fit.” It was too steep for me to see what was below him, other than the vertical nothingness indicative of a huge cliff. He couldn’t see immediately below him from where he was either, triggering the unwritten rule of “don’t ski what you can’t see” or “don’t go if you don’t know.” So I told him to stay put while I quickly pondered our dilemma.

Since hiking up was not an option for him, we had two choices. Either I could ski down to him against his advice and try to figure things out from there, at least suffering our fate together. Or I could hold my position and call for help. Having been cliffed-out myself multiple times over the years, each time swearing to myself “never again,” I took what I thought was the more conservative approach. I called 911 who connected me through the police to Snowbird Ski Patrol. Describing our remote location as best I could, they were able to get our GPS coordinates from my cell phone, and the ski patrol confidently said one of their best rescue guys was on his way with ropes and more. As I kept telling Jason not to budge, my mind was racing with scary scenarios and guilt-ridden thoughts. Luckily it was before noon, help was on the way, and he seemed to be handling the situation remarkably well.

Suddenly two skiers appeared above us out of nowhere, extreme locals as it turned out. Still on my cell with ski patrol and afraid they’d unload a pile of snow on top of him, I yelled “don’t ski there, my son’s stuck on the cliff below.” Staying left of Jason’s fall line, the first guy swooped down to him, dug in, and literally lifted him uphill a few feet up the cliff, flipping him over so his skis were wedged into a small tree, just to the skier’s left of the cliffs. Trying to calm my evident fear, he half-jokingly said “he probably wouldn’t have died,” to which I retorted “that’s comforting.” Then the local realized he was in a pretty bad position himself, but through an acrobatic maneuver he was able to get up and away from the cliff. Still not knowing what was next, I was unsure whether I should stop this possible hero from helping further since the patroller would presumably be with us in 10-15 minutes. It didn’t seem right though to interrupt a deus ex machina midstream, and the next thing I knew the rescuer had disappeared above the cliff band through some small trees with Jason closely behind saying “I can do that,” followed a couple minutes later by hearing him far below yell “Dad, I’m ok.”

With an enormous sigh of relief, the revelation hit me that the bracing sensation of safety can trump even the sweet smell of success. The other local and I skied further across the Knucklehead (Red Lens) Traverse line comfortably above the cliffs, before dropping into Defiance Ledge and then meeting up with Jason in Figure Eight Gully far below. With my sense of profound relief still peaking, I looked up and finally saw the gigantic cliff where Jason had been perched while contemplating the magnitude of the bullet we had just dodged. The ski patroller, whom I had already called right after Jason escaped the imminent danger, was now above the cliffs looking down at us. As I stared at Jason with the infinity of love, he intuitively sensed my heartfelt relief and said “Dad, we made it, let’s enjoy the powder on the rest of this run.”

Fully cognizant that luck had been on our side, we thoroughly reveled in the remainder of the glorious day, with even monumental runs like Dalton’s Draw seeming tame in comparison. Neither of us could stop talking or thinking about what we’d just experienced, and we agreed on a set of future lessons including: don’t get cliffed-out again, know when to rely on the kindness of strangers, don’t ski below a remote steep traverse line unless you know what lurks below and, above all, don’t panic in the face of danger. An epic day had broadened into a lifetime experience.

MarcT

April 2011

Pushing the envelope. Ski posse; Marc T. and Jason.

Aspen Spin |

Aspen Spin |  3 Comments |

3 Comments |